Marshall McLuhan fellow and ABS-CBN Filipina journalist speaks on free press and press freedom during Mass Com Week

Marshall McLuhan Fellow Karmina Constantino, veteran Filipina journalist, speaks during the Mass Com Week Celebration at the Audio-Visual Theater, Silliman University.

Marshall McLuhan Fellow Karmina Constantino, veteran Filipina journalist and news anchor for Dateline Philippines, a flagship of ABS-CBN News Channel (ANC), and the radio station DWPM Radyo Sais Trenta, spoke on “Free Press and Press Freedom” for the 2024 Marshall McLuhan Forum Series on Responsible Media, an event in collaboration with Silliman University (SU) College of Mass Communication (CMC) and The Embassy of Canada, at the Audio-Visual Theater on March 7, 2024.

Opening her talk with a string of short clips featuring some promotional videos of politicians and elected officials, Constantino forewarned about how these candidates will turn to social media and how this will go on overdrive once the midterm elections come.

“They learned from the last elections and the elections before that about the power of social media, and they are going to use it even more. These politicians will be talking directly to the public, engaging them, making sure you are their captured audience, from the time you guys press ‘Play’ until the video ends without an iota of challenge to every word that leaves their mouth, whether it’s fact or fiction,” opened Constantino.

In the midst of an era of information overdrive propelled by technology, particularly social media, comes the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation, “where facts are made irrelevant, where there is disregard for history, where importance is placed more on opinion rather than correct information, where power and popularity dictate the truth.”

“It happened before and it’s going to happen again. And it’s going to be even more potent,” she warned.

“Sa mga panahon ngayon, mas makapangyarihan ang mga marites [In these times, gossipmongers hold more power]. And caught in the snares of this toxic post-truth era is us, the public,” Constantino added.

Press freedom and democracy

Constantino recalled how the public used to readily rely on “a band of truthseekers [or] storytellers to give them a complete narrative.” Those days were long over.

Along with the rise of social media, journalists have become targets themselves not only of hate but also, unfortunately, of killings, whose existence is always put into question through attacks made by those, Constantino argued, who want democracy dead.

According to the Human Rights Foundation, there had been 32 incidents of red-tagging and at least 23 journalists killed between 2016 and 2022. From 2016 to 2022, the Philippines, under the administration of Rodrigo Duterte, gradually slid back into authoritarianism.

“Democracy, you might ask, what does that have to do with journalism? Why are we talking about freedom when we were [just] talking about facts?” asked Constantino, zeroing in on the heart of the matter.

She reminded the audience of her role – like all journalists’ – which is to reintroduce and defend the role of journalists and why they shouldn’t be the only ones fighting for freedom because, as Constantino said, “To fight for ours is to fight for yours, too.”

Philippine media from 1945 to 1972

But there was a time when this fight against silence and censorship wasn’t always the case, maintained Constantino.

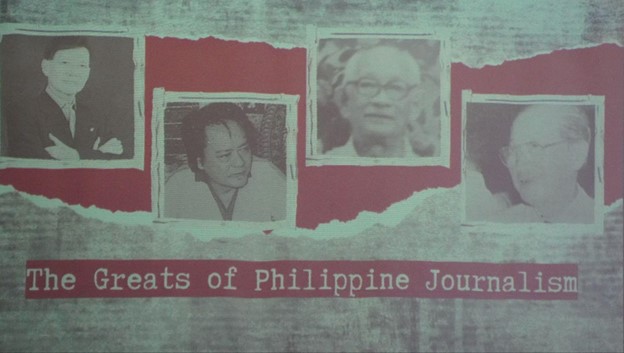

Photo courtesy of Karmina Constantino during her presentation.

“There was a moment in our nation’s history when the media was considered the freest in Asia. Between the years 1945 and 1972, Philippine media was celebrated enough to call it its Golden Age. Within this time [was] the rise of radio, primarily as a tool to inform the public about postwar recovery efforts,” she explained.

This period saw an “almost frenetic growth of every aspect of free press.” It was around this time, too, that the Philippine Press Institute was established “to foster the development and improvement of journalism in our country.” It was also the period where the “greats of Philippine journalists” were produced and journalism courses were offered to train the future watchdogs of the free.

“During this time, the roles were clear. Government governs, while the press keeps watch,” Constantino said.

The first shutdown

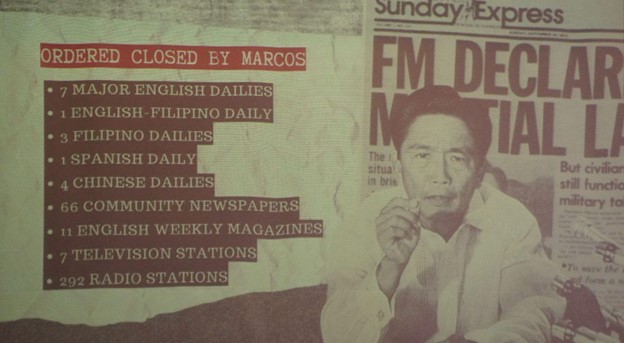

The late president Ferdinand Marcos Sr. declares Martial Law and closes the media. Photo courtesy of Karmina Constantino during her presentation.

The late dictator and president Ferdinand Marcos Sr., father of the incumbent President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., maintained power by declaring Martial Law on September 21, 1972, which allowed the dictator to control history on his own terms and ensconce himself as president for 20 years.

“Darkness descended on the Philippines. All of a sudden, liberties were curtailed. All of a sudden, voices were muffled. All in the name of defending the people of the Republic,” said Constantino, referring to Marcos’ statement during his declaration of Martial rule, “All that I do and we, in government, must do is for the Republic and you.”

Indeed, Marcos used Martial Law to quell insurrections and stop the rebellions.

“At least, that’s what he said,” Constantino retorted. But it was also, in reality, meant to stifle the growing dissent of the people, ultimately killing democracy and, with it, the press.

Killing the press meant ordering the closure of newspaper offices, TV, and radio stations. In numbers, seven (7) major English dailies, one (1) English-Filipino daily, three (3) Filipino dailies, one (1) Spanish daily, four (4) Chinese dailies, 66 community newspapers, 11 English weekly magazines, seven (7) television stations, and 292 radio stations were all ordered to shut down.

Among these TV stations was ABS-CBN. The year 1972 would mark the very first time in its history that the station would be ordered to shut down.

The rise of alternative press

A few years into the dark days of Martial Law, the alternative press was born, thanks to Joe Burgos, in order to pierce through the lies and propaganda spun by the mainstream and state-approved media.

The renowned Joe Burgos. Photo courtesy of Karmina Constantino during her presentation.

Constantino emphasized, “Walang kapangyarihan ang mas hihigit pa sa mga mamamahayag na gustong maging malaya [No shackles are strong enough against a free press determined to be free].”

“Joe Burgos [together with his wife] started to strip away the lies being spun by the Marcos administration, publishing pieces that were biased, yes, for the truth. Even when Joe knew that he and his comrades were chronicling and sailing too close to the wind, he soldiered on.”

Soon enough, many followed suit. Entertainment magazines published scathing critiques of the Marcos administration, camouflaged by the faces of young superstars and celebrities gracing the covers of these glossy magazines.

Other revolutionary papers during the Marcos rule (e.g., WE Forum, Mr. & Ms. Special Edition, The Philippine Collegian, among others) remained unyielding in their pursuit of the truth.

“And Marcos, he let them be because the dictator didn’t want to appear to be one. To make it seem that the Marcos [presidency] was thriving under a dictatorial rule, then President Marcos ‘allowed’ these publications to exist, but not without the threat of being charged with sedition,” added Constantino.

Marcos belittled the alternative press by comparing them to pesky insects, which earned them this alternative media, the Marcos-given moniker, ‘mosquito press.’

With every published piece from these alternative publications came the poison it wrought to the Marcos administration. Courage stirred in the public who was slowly awakening to the ills and evils of the dictatorship.

The press amidst ousted presidents

The People Power Revolution ousted the dictator, and, according to Constantino, this wouldn’t have happened without the press.

“But here’s the thing, as striking as all of this may seem, it would only be the first time a sitting president of the Republic would be ousted partly because of the courageous reporting of the media,” Constantino pointed out.

Mike Ramo, Malinawon Media Club president and DYMD-Energy FM program director and radio show host, speaks as one of the lecture reactors. Next to him are Jennifer Catan-Tilos, manager of the Philippine Information Agency in Dumaguete and Mac Florendo, SU CMC alumnus.

In 2021, the Philippines’ 13th president would meet the same fate. Former President Joseph Ejercito Estrada, whose election campaign read, “Erap para sa mahirap [Erap for the poor],” won the presidency by a large margin. Two years into his presidency, however, allegations of corruption began to surface.

The press reported on every lead, recorded history, and took photos and recordings from the time the first allegation was made, all the way through the 20-day impeachment trial, until the “Prince of the Paupers” was finally ousted.

Then came former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo who took the helm from her predecessor, Estrada, and was the face of the opposition then. Arroyo’s presidency was mired by several controversies, including allegations of corruption, her husband’s business dealings, the misuse and mismanagement of public funds, the vote-rigging scandal, and the alleged bribes given to lawmakers to buy legal protection and stop an impeachment complaint. In all of this, the media was there, exposing every detail.

Arroyo finished her term, surviving three (3) impeachment trials. To this day, she remains a member of the Congress.

“Journalism plays a crucial role in every nation’s democratic development. For us here in the Philippines, without the mosquito press, without the exposé about corruption and election manipulation, throughout just these three administrations, where do you think the Filipino public would be now? Where would democracy be?” asked Constantino.

“Information is so crucial that it doesn’t just get power to the people, but it holds the powerful to account,” she added.

The second shutdown

All this led Constantino to reflect on the state of journalism and journalists today.

Karmina Constantino presents a clip of the press interview with former president Rodrigo R. Duterte.

“I stand before you today, a remnant of what was once a busy and bustling newsroom. It seems like a distant memory now, but let me tell you, the pain is still as fresh as when right in the middle of a raging pandemic, ABS-CBN, the largest broadcasting corporation in the country, was shut down. And that was the second time in its history. The force behind it, number 16,” continued Constantino.

Former president Rodrigo R. Duterte, the sixteenth president of the Republic, is known not only for his cuss-filled rhetoric but also for his pledge to annihilate criminals in his promises of brutal but quick solutions to the country’s perennial problems of crime and poverty.

Duterte also endorsed the killing of corrupt journalists. When asked how he would plan to address media killings in the country, he maintained that journalists who took bribes or engaged in other corrupt activities also deserved to die.

“Just because you’re a journalist you are not exempted from assassination, if you’re a son of a [explication],” Duterte said in an interview with a media outlet.

Because the media were critical of him, Constantino thought it only natural for the former president to be critical of the media as well.

“But here’s the thing, he was president. And he had the whole government at his disposal to turn this criticism of the media into a massive monster. In fact, he did. From criticisms that went on to being outright attacks, he called the media paid hacks. He had vloggers supportive of him, echoing his description of the media,” she said.

Some of these criticisms included infamous descriptions such as “presstitutes,” “bayaran,” “bias,” “dilawan,” reverberating through social media and reaching millions of Duterte’s followers and avid supporters. In tandem with this raucous was the former president’s war on drugs, normalizing a mounting of dead people on the streets to which “he exclaimed it was necessary, that it was a matter of the country’s survival.”

Karmina Constantino answers some questions from students during the open forum.

“When rights defenders made their voices heard, he invalidated them by asking, Whose rights are you defending anyway? Are you defending the rights of the victims of the illegal drug trade or the rights of the criminals behind the illegal drug trade?” Constantino said.

In the same tone, Constantino examined Duterte’s use of deceptive rhetoric when he said, “Kill them all,” aimed to mislead the public and convince them that occurrences such as the sudden appearances of dead bodies on the streets and suspects dying in police operations were normal. She argued that Duterte deceived his followers into accepting that thousands of deaths in the name of the drug war as justifiable, and diminished the value of human rights. She also added that Duterte’s role in allowing the burial of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Libingan ng mga Bayani [Cemetery of Heroes] marked the initiation of an institutionalized effort to whitewash a dark chapter in Filipino history.

“This disregard for history and hard facts coupled with disinformation fueled by the tough talk of the president himself made his government virtually an unstoppable force. So when ABS-CBN, my home network, was ordered shutdown, the public could only stare at the screens in disbelief,” she said.

The new entity

On May 5, 2020, a day after its 25-year franchise expired and forty-eight (48) years after its first closure, the National Telecommunication Commission, which is part of Duterte’s office, ordered the closing of ABS-CBN.

“We are still reeling from it. Fact is, last June 29, [this happened while I was touring in Canada] ABS-CBN had to shut down the operations of Teleradyo. Teleradyo was what remained of DZMM, our AM radio station. When we lost the franchise, Teleradyo continued to air through other channels and online. But the revenue from ads, it wasn’t coming in big enough and fast enough.”

Constantino recalled how they had to let go of people and do several more layoffs. But it still wasn’t enough, saying the “loss proved to be too much. Hindi na talaga nakayanan [Nothing else could be done].”

The franchise owners, the Lopezes, decided to go on a joint venture with another entity to survive.

“And what we have right now is a new creature. Part ABS-CBN, part Prime Media—the other entity. And that’s associated with the speaker of the house, cousin of the [incumbent] president of the country.”

With this new proximity to the palace, Constantino asked herself if she could still muster the courage to go on.

“The only way to know if my fears are well founded is to test it. And so far, eight months down the line, I’m still asking the tough questions on air,” Constantino said, believing that her job as a journalist is to continue to hold the powerful to account, no matter the administration.

“It’s not about courage. It’s about doing what is right,” she added.

The Marshall McLuhan Fellowship

Constantino has been a journalist for more than twenty-five (25) years. She is the granddaughter of historian Renato Constantino and the daughter of activist Renato Constantino Jr.

Public Affairs Attaché Carlo Figueroa of The Embassy of Canada, in his introduction of Constantino, said, “The Canadian Embassy awarded her the McLuhan Fellowship in 2022 for her ‘unflinching commitment to speak truth to power, an admirable consistency in ferreting out the most complicated issues of the day, and a stirring courage to ask the toughest questions.’”

Established in 1997, the prestigious Marshall McLuhan Fellowship is awarded annually by the Canadian Embassy in the Philippines to a recipient “embodying outstanding qualities in the field of investigative journalism.”

Carlo Figueroa answers a question from one of the students during the open forum.

Constantino’s tour in Canada in 2023 as part of her fellowship included a lecture series in several cities on the topic, “Revisiting the Basics: The Role of the Journalist in Critical Public Discourse.” This particular talk at SU for the Mass Com Week was a version of the talk she delivered in Canada but “tailored to the local context.”

“Her work is commendable for raising the bar in Philippine journalism and has been setting the standard for how journalists should bravely ask their questions,” Figueroa said in his message.

“Her work shows us how responsible journalism makes a vital contribution to elevating the social discourse and issues with national and international importance,” he added.

This is the 17th year that The Embassy of Canada has partnered with Silliman University in delivering the Marshall McLuhan Forum. Figueroa hopes to expand “this activity and other media-related, capacity-building initiatives in the next few years.”

The SU College of Mass Communication students and The Weekly Sillimanian staff together with Asst. Prof. Melita C. Aguilar and Karmina Constantino after the event.

The lecture forum was part of the college’s Mass Com Week celebration. In his welcome address, Dr. Earl Jude Paul L. Cleope, SU vice president for Academic Affairs (VPAA), recognized the importance of the gathering and acknowledged Constantino’s capacity “to guide… [the audience] to engage in thoughtful discourse on the pivotal role of responsible media in our society.”

SU Vice President for Academic Affairs Dr. Earl Jude Paul L. Cleope opens the forum with an introduction of the guest speaker.

Also present at the event were SU CMC Dean Dr. Madeline B. Quiamco, The Weekly Sillimanian (tWS) Adviser Asst. Prof. Melita C. Aguilar together with the tWS staff and CMC students, SU Church Senior Minister Rev. Jonathan R. Pia, other friends from the media in the city, and friends of the Silliman community, including Mass Communication students from Foundation University and Negros Oriental State University.

The event also invited lecture reactors Jennifer Catan-Tilos, manager of the Philippine Information Agency in Dumaguete; Mike Ramo, Malinawon Media Club president and DYMD-Energy FM program director and radio show host; Mac Florendo, SU CMC alumnus; and Renz Macion, former SK Federation president, SU CMC alumnus, and Philippine representative for the 2024 Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (YSEALI) Academic Fellowship program.

Left to right: Lecture reactors Renz Macion, Mac Florendo, Mike Ramo, and Jennifer Catan-Tilos pose with SU CMC Dean Dr. Madeline B. Quiamco, Karmina Constantino, Public Affairs Attaché to The Embassy of Canada Carlo Figueroa, and tWS Adviser Asst. Prof. Melita C. Aguilar after the giving of certificates.

Constantino gave a lecture on “The Art of Interviewing” to local campus journalists in the afternoon after her talk.