The Road to Zero Waste

The Road to Zero Waste: Part I

The cities of the world generated 1.3 billion tons of solid waste in 2012, an amount expected to nearly double by 2025. Last year, Dumaguete contributed about 24,900 tons or 124,000 cubic meters of waste, of which more than 65,600 cubic meters (including Silliman’s 415 truckloads) were dumped in the Candau-ay dumpsite.

Our dumpsite has been a festering blight on the city. Its stench wafts over four barangays and its putrid mass towers over the broken embankment of the Banica River. Since 1965, every rainfall has caused toxic chemicals, disease-causing microbes, and other pollutants to percolate into the groundwater or flow directly into the Banica, as evidenced by the dark liquid constantly seeping from the waste pile.

I took these photos last July 13. One shows the garbage heap, which rises 12 meters above the road. The other shows what you probably already know: a huge bulk of our waste is comprised of plastics.

But here is something you may not know. With time, plastic waste releases the toxic substances used in their manufacture, such as phthalates and bisphenol A (which interfere with hormones in the body and can cause cancer) and organotin compounds (which can affect the central nervous system). Moreover, plastics break up into microplastics that attract many contaminants known to cause tumors and birth defects.

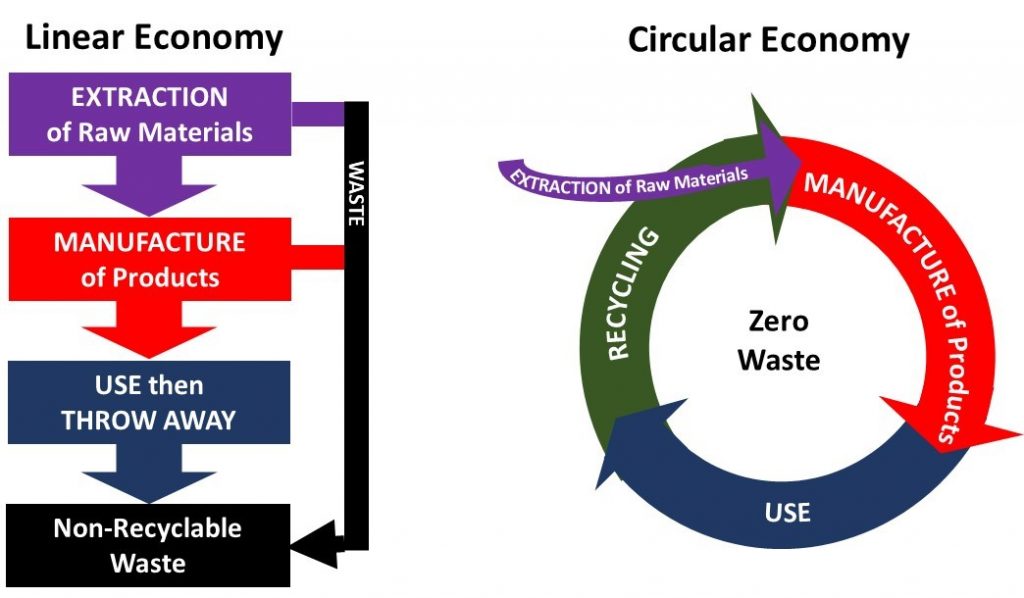

The environmental crisis we face today is very much a product of how we have developed as a society. Since the industrial revolution, we have embraced a linear pattern of consumerism characterized by the extraction of natural resources, manufacture of products, disposal of waste, followed by more extraction, manufacture, and disposal ad infinitum, on the false assumptions that the earth’s resources are infinite and that land, sea and air are so vast that dumping our wastes would have no consequences. Now we know better.

Past attempts at solving the problem have been piecemeal and narrowly focused, a Band-Aid solution on an uncontrolled hemorrhage. Those that have examined the root causes have come to realize the perils of linear consumption and a throwaway culture, concluding that humanity must shift towards a circular model of development that is instead restorative and regenerative.

Circularity entails closing material loops by redesigning manufacturing processes, materials, products, and systems to eliminate waste at all stages. A circular economy uses clean production methods and clean energy to make consumable products that can safely return to the biosphere and durable products that are intended for multiple reuse, easy repair or refurbishment, disassembly and remanufacturing.

This is the philosophy behind the global movement for Zero Waste, based on the most successful model of all—nature. Zero Waste is a goal that requires changes in lifestyles and practices to emulate sustainable natural cycles. Some have asked me to predict if this is what the future holds. The best way to predict the future is to create it ourselves. It may take a generation to fully achieve this transformation but the journey to Zero Waste must begin now.

The Road to Zero Waste: Part II

Today, thousands of communities worldwide have committed to Zero Waste (ZW) principles and are moving towards ZW. In the United States, ZW cities (with target years) include: San Francisco (2020), Los Angeles (2025), and New York (2030). They are joined by cities as diverse as Bandung, Indonesia; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Alleppey, India; Vancouver, Canada; Kamikatsu, Japan; Canberra, Australia; and Ljubljana, Slovenia—the first ZW capital city in Europe.

The Philippine ZW cities are San Fernando, Pampanga; Navotas, Malabon and Fort Bonifacio (Taguig) in Metro Manila; General Mariano Alvarez, Cavite; Batangas City, Batangas; and others. ZW in practice today means diverting 90% of waste away from landfills and incinerators, a step towards a circular economy.

This July, three barangays in Dumaguete (Looc, Bantayan, and Piapi) start transforming into ZW communities. They will adopt a process, developed by Mother Earth Foundation, that entails: assessments, consultations, training, organization, planning, policies, materials recovery facilities, information/education campaigns, implementation of ZW systems, monitoring, enforcement, and continuous improvement.

ZW requires waste prevention, segregation at source, separate collection, maximum reuse and recycling, composting, and reduction of residual waste by enforcing City Ordinance 231 regulating plastic bags and Styrofoam. These may be supplemented by bans on plastic straws and packaging.

President Betty McCann advocates for Silliman to be a Zero Waste university, perhaps the first in the nation. What does it mean to be a ZW campus? Practically speaking, it means reducing our residual waste (what will go to our dumpsite) down to 10% of our total waste. Achieving this requires engaging the entire Silliman community.

Through labels, posters, and information campaigns, everyone will have to know how to segregate recyclables, biodegradables, and residual waste. Buildings & Grounds will collect recyclables separately and work with local junkshops. Biodegradables will be collected frequently and returned to nature via composting, vermi-composting, and biodigestion. The rich compost and vermicast will be used to enrich our soils, and some could go to local farmers.

We will establish our baseline and develop policies and plans. We have to adopt purchasing policies that reduce waste and plastics. We may have to ban sachets and encourage buying products in larger volumes. We will work with food vendors and concessionaires, and make our events, such as the Hibalag Festival, models of ZW.

Silliman is not starting from scratch. We already have green spaces which enhance the livability and health of our city. Many student residences already segregate. The cafeteria already sends its leftover food to piggeries, has gotten rid of plastic straws, offers drinking water in dispensers, and uses compostable wrappings like banana leaves. Many of our trash bins are already color-coded. Some students already bring their own reusable bags and drinking bottles. Plans to turn Silliman Beach into an eco-park are ongoing. But more needs to be done and the work must be systematic.

As Silliman University transforms, so too must individual lifestyles. To be stewards of creation, every Sillimanian will have to choose: Will you be part of the problem or part of the solution?